It’s been nearly three months since I released my first book, Secure Meteor. Time has flown, and I couldn’t be happier with how it’s been embraced by the Meteor community. In the early days of creating Secure Meteor (and the middle days, and the late days…), I wasn’t sure about the best way of actually writing a self-published, technical ebook.

I’m not talking about how to come up with the words and content. You’re on your own for that. I’m talking about how to get those words from my mind into a digital artifact that can be consumed by readers.

What editor do I use? Word? Emacs? Ulysses? Scrivener? Something else?

If I’m using a plain-text editor, what format do I write in? Markdown? If so, what flavor? LaTeX? if so, what distribution? HTML? Something else?

How do I turn what I’ve written into a well typeset final product? Pandoc? LaTeX? CSS? Something else?

The fact that you can purchase a copy of Secure Meteor is proof enough that I landed on answers to all of these questions. Let’s dive into the nuts and bolts of the process and workflow I came up with to create the digital artifact that is Secure Meteor!

Please note that I’m not necessarily advocating for this workflow. This process has taught me lots of lessons, and I’ll go over what I’ve come to believe towards the end of this article.

Writing in Scrivener

I’ve been a long-time user of Ulysses; I use it to write all of my online content. That said, I wasn’t sure it was up to the task of writing a several-hundred page technical book. I had heard wonderful things about Scrivener, so I decided to try it out on this project.

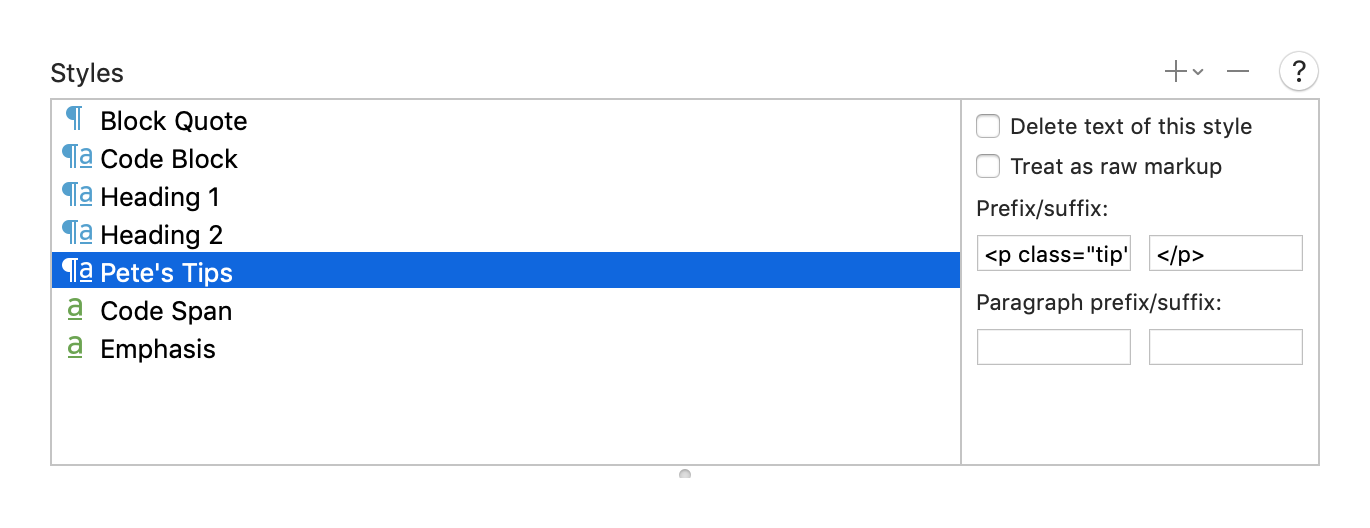

At its heart, Scrivener is a rich-text editor. To write Secure Meteor, I used a subset of Scrivener’s rich-text formatting tools to describe the pieces of my book. “Emphasis” and “code span” character styles were used for inline styling, and the “code block” style was used for sections of source code.

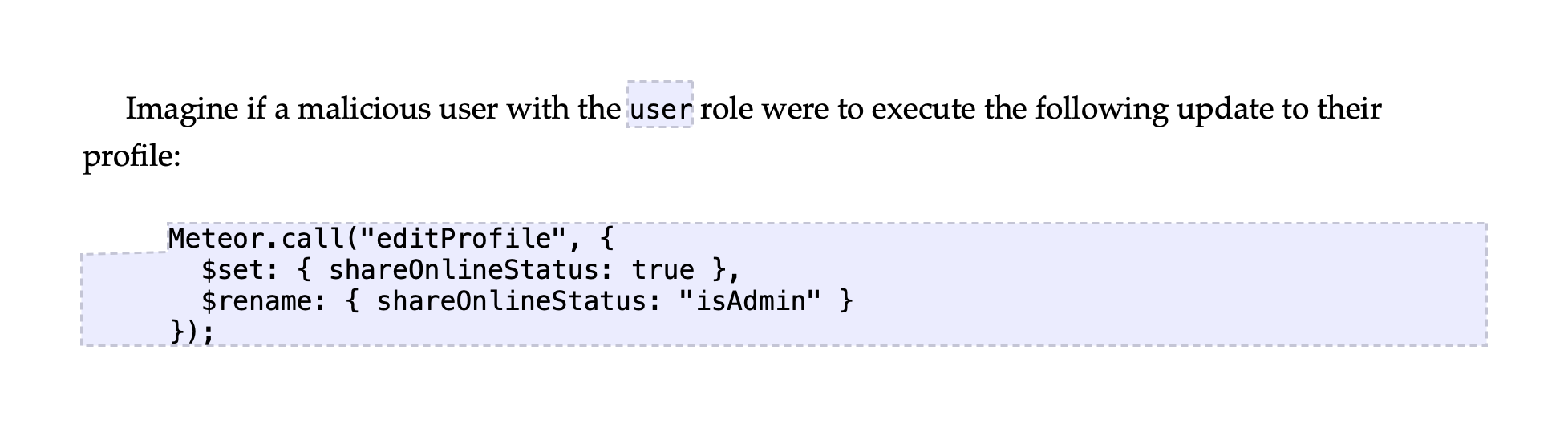

For example, this section of text in Scrivener:

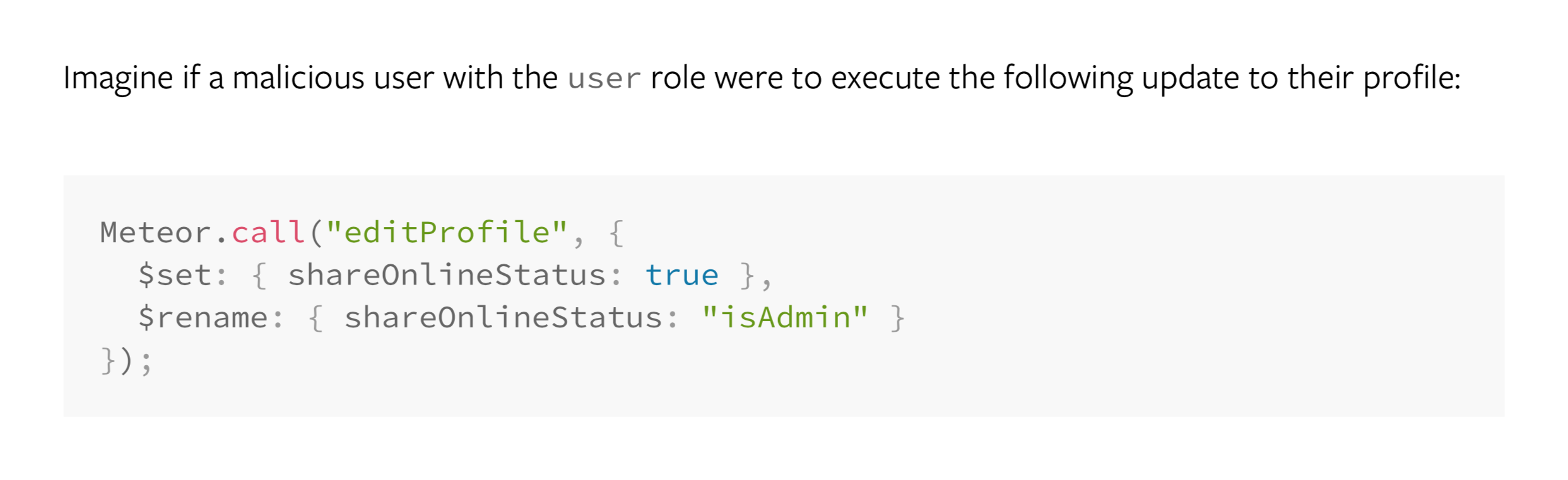

Eventually looks like this in the final book:

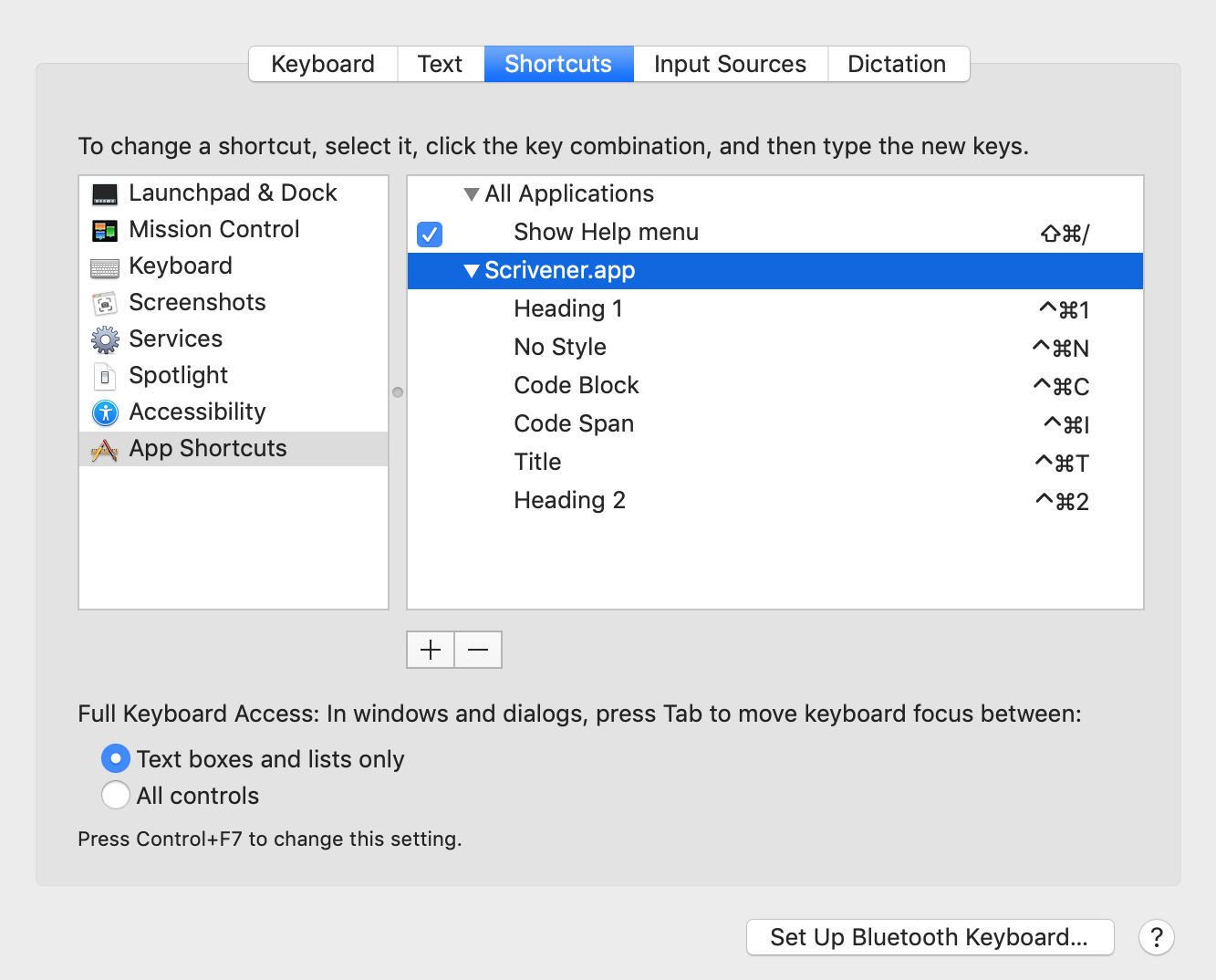

I added a few application keyboard shortcuts to make toggling between these styles easier:

With those shortcuts I can hit ^⌘I to switch to the inline “code span” style, ^⌘C to switch to a “code block”, and ^⌘N to clear the current style. Scrivener’s built-in ⌘i shortcut for “emphasis” was also very helpful.

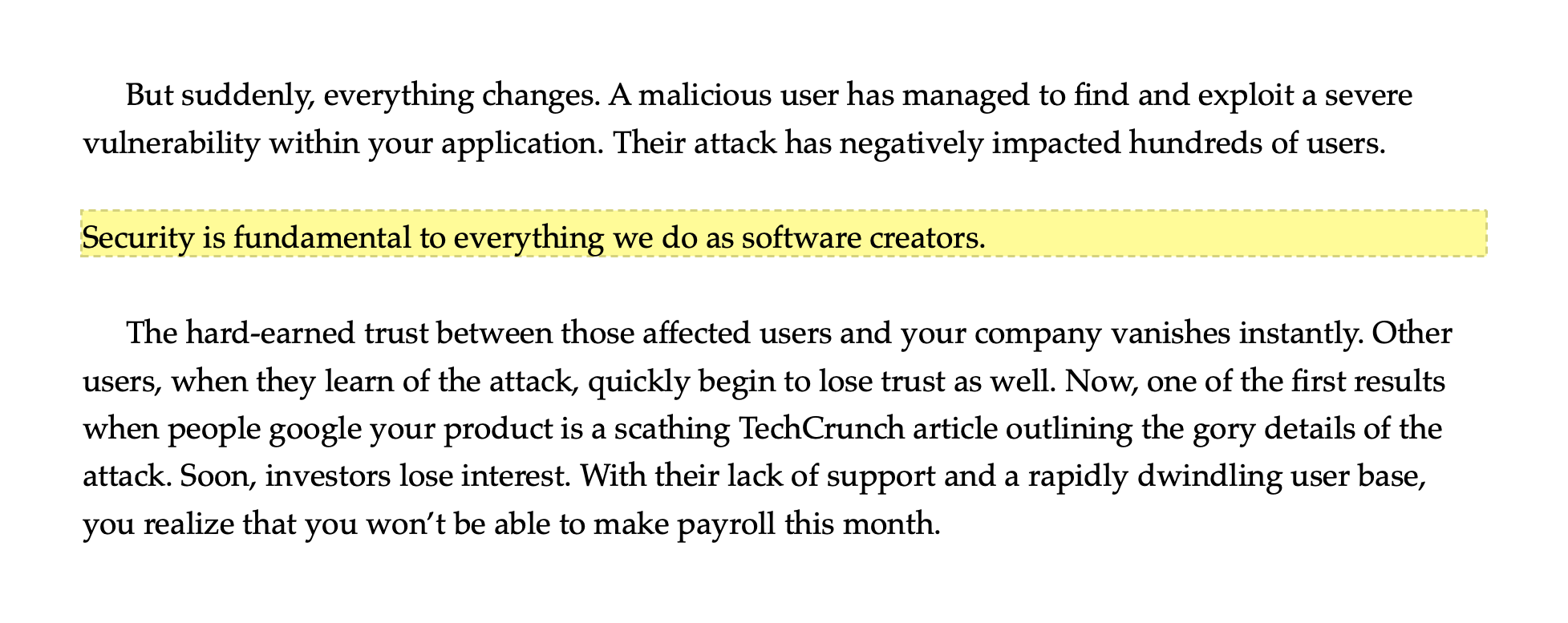

I also added a custom “Pete’s Tips” paragraph style which is used to highlight callouts and points of emphasis throughout various chapters. In Scrivener, my tips are highlighted in yellow:

And in the final book, they’re floated left and styled for emphasis:

Organizing Content

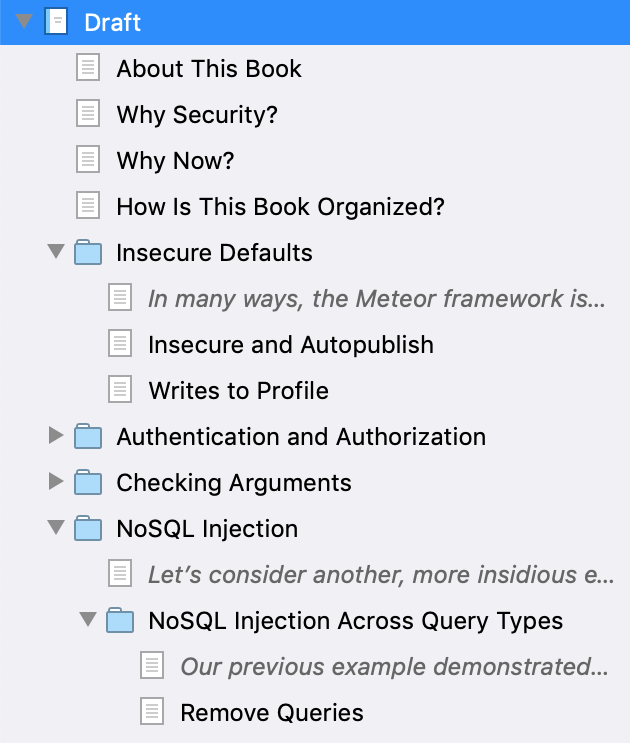

In the early days, I was lost in the various ways of organizing a Scrivener project. Should I have one document per chapter? Should I have a folder per chapter and a document per section? Should I use the “Title”/”Header 1”/”Header 2” paragraph styles with unnamed Scrivener documents, or should I just use document names to indicate chapter/section names?

Ultimately I landed on a completely hierarchical organization scheme that doesn’t use any “Title” or “Header” paragraph styles.

Every document in the root of my Scrivener project is considered a chapter in Secure Meteor. Chapters without sub-sections are simply named documents. Chapters with sub-sections are named folders. The first document in that folder is unnamed, and any following sub-sections are named documents (or folders, if we want to go deeper).

This organization scheme worked out really well for me when it came time to lay out my final document and build my table of contents.

Scrivomatic

Unfortunately, Scrivener’s compiler support for syntax-highlighted code blocks isn’t great (read: non-existent). If I wanted my book to be styled the way I wanted, I had no choice but to do the final rendering outside of Scrivener.

I decided on using Pandoc to render my book into HTML, and found Scrivomatic to be an unbelievably useful tool for working with Pandoc within the context of a Scrivener project.

After installing Scrivomatic and its various dependencies, I added a “front matter” document to my Scrivener project:

---

title: "<$projecttitle>"

author:

- Pete Corey

keywords:

- Meteor

- Security

pandocomatic_:

use-template:

- secure-meteor-html

---

After adding my front matter, I added a “Scrivomatic” compile format, once again, following Scrivomatic’s instructions. It’s in this compile format that I added a prefix and suffix for “Pete’s Tips” paragraph styles that wraps each tip in a <p> tag with a tip class:

Next, I added the secure-meteor-html template referenced in my front matter to my ~/.pandoc/pandocomatic.yaml configuration file:

secure-meteor-html:

setup: []

preprocessors: []

pandoc:

standalone: true

metadata:

notes-after-punctuation: false

postprocessors: []

cleanup: []

pandoc:

from: markdown

to: html5

standalone: true

number-sections: false

section-divs: true

css: ./stylesheet.css

self-contained: true

toc: true

toc-depth: 4

base-header-level: 1

template: ./custom.html

Note that I’m using ./custom.html and ./stylesheet.css as my HTML and CSS template files. Those will live within my Scrivener project folder (~/Secure Meteor).

Also note that I’m telling Pandoc to build a table of contents, which it happily does, thanks to the project structure we went over previously.

My custom.html is a stripped down and customized version of Scrivomatic’s default HTML template. To get the styling and structure of my title page just right, I built it out manually in the template:

$if(title)$

<header id="title-block-header">

<div>

<h1 class="title">Secure Meteor</h1>

<p class="subtitle">Learn the ins and outs of securing your Meteor application from a Meteor security professional.</p>

<p class="author">Written by Pete Corey.</p>

</div>

</header>

$endif$

My CSS template, which you can see here, was also based on a stripped down version of Scrivomatic’s default CSS template. A few callouts to mention are that I used Typekit to pull down the font I wanted to use:

@import url("https://use.typekit.net/ssa1tke.css");

body {

font-family: "freight-sans-pro",sans-serif;

...

}

I added the styling for “Pete’s Tips” floating sections:

.tip {

font-size: 1.6em;

float: right;

max-width: 66%;

margin: 0.5em 0 0.5em 1em;

line-height: 1.6;

color: #ccc;

text-align: right;

}

And I set up various page-break-* rules around the table of contents, chapters, sections, and code blocks:

#TOC {

page-break-after: always;

}

h1 {

page-break-before: always

}

h1,h2,h3,h4,h5,h6 {

page-break-after: avoid;

}

.sourceCode {

page-break-inside: avoid;

}

My goals with these rules were to always start a chapter on a new page, to avoid section headings hanging at the end of pages, and to avoid code blocks being broken in half by page breaks.

Generating a well-formatted HTML version of my book had the nice side effect of letting me easily publish sample chapters online.

HTML to PDF

Pandoc, through Scrivomatic, was doing a great job of converting my Scrivener project into an HTML document, but now I wanted to generate a PDF document as a final artifact that I could give to my customers. Pandoc’s PDF generation uses LaTeX to typeset and format documents, and after much pain and strife, I decided I didn’t want to go that route.

I wanted to turn my HTML document, which was perfectly styled, into a distributable PDF.

The first route I took was to simply open the HTML document in Chrome and “print” it to a PDF document. This worked, but I wanted an automated solution that didn’t require I remember margin settings and page sizes. I also wanted a solution that allowed me to append styled page numbers to the footer of every page in the book, aside from the title page (which was built in our HTML template, outside the context of our Scrivener project and our generated table of contents).

I landed on writing a Puppeteer script that renders the HTML version of Secure Meteor into its final PDF. There are quite a few things going on in this script. First, it renders the title page by itself into first.pdf:

await page.pdf({

path: "first.pdf",

pageRanges: "1",

...

});

Next, it saves the rest of the pages to rest.pdf, including a custom footer that renders the current page number:

await page.pdf({

path: "rest.pdf",

pageRanges: "2-",

footerTemplate: "...",

...

});

Finally, first.pdf and rest.pdf are merged together using the pdf-merge NPM package, which uses pdftk under the hood:

await pdfMerge([`${__dirname}/first.pdf`, `${__dirname}/rest.pdf`], {

output: `${__dirname}/out.pdf`,

libPath: "/usr/local/bin/pdftk"

});

By rendering the title separately from the rest of the book we’re able to place page numbers on the internal pages of our book, while keeping the title page footer free. This is another reason for building the title page into our HTML template. If we built it with Scrivener, Scrivomatic would count it as a page when generating our table of contents, which we don’t want.

Fine Tuning Page Breaks and Line Wraps

Finally, I had a mostly automated process for going from a draft in Scrivener to a rendered PDF. I could compile my Scrivener project down to HTML and then run my ./puppeteer script to generate a final PDF.

After looking through this final PDF, I realized that it still needed quite a bit of work.

Some code blocks overflowed out of the page. I went through each page, looking for these offending blocks of code and manually trimmed them down to size by truncating lines cleanly at a certain character count, when appropriate, or by adding line breaks where possible.

I also noticed many unaesthetic page breaks: section headers too close to the bottom of a page, large gaps at the bottom of pages caused by subsequent large code blocks, poorly floated “Pete’s Tips”. I had no choice but to start on page one and work my way through each of these issues.

I didn’t want to change the text of the book, so my only choice was to manually modify the generated HTML and add page-break-* styles on specific elements. Eventually, I massaged the book into a form I was happy with. Unfortunately, any changes I make to the text in Scrivener will force me to redo these manual changes.

Eventually, I had my final PDF. If you’d like to see how it turned out, go grab a copy of Secure Meteor or check out a few of the sample chapters!

Final Thoughts

I’m a few months removed from this whole process, and I have far more thoughts now than I did when I first started.

Would I use this workflow to write another book? Probably not. For all of Scrivener’s power, I don’t think rich-text editing is my jam. I’m more inclined to use Ulysses, which I know and love, to write in a plain-text format. If I had to choose today, I’d write in a flavor of Markdown or begin my journey up LaTeX’s the steep learning curve.

I also need to find a better renderer than a browser. There’s a whole host of CSS functionality that’s proposed or deprecated that would make rendering paged media in the browser more feasible, like CSS-only page numbers, orphans and widows, and more, but none of it works in current versions of Chrome and Firefox. Prince seems to promise some of this functionality, but its price tag is too steep for me. Then again, working directly with LaTeX seems like it would aleviate these problems altogether.

Ultimately, I wanted to document this process because figuring this stuff out was ridiculously difficult. Writing the words of the book was easy in comparison. Hopefully this will act as a guide to others to show what’s currently possible, and some potential pitfalls to avoid.